Limiting Pharma Rep's Access to Docs (Surprise!) Reduces Prescriptions

/For the video version, click here.

If you work at a hospital like mine, it’s probably been a long time since you’ve been treated to a lavish, educational dinner sponsored by a pharmaceutical company. It’s probably been a while since you’ve seen a pen with a drug name on it, actually. There’s a reason for that, due to policies coming from Pharma itself, and individual medical centers. The question is, do these policies that limit physician-pharmaceutical rep interaction actually change prescribing practices? That question is addressed, in as thorough a manner as I’ve ever seen, in this article, appearing in the Journal of the American Medical Association.

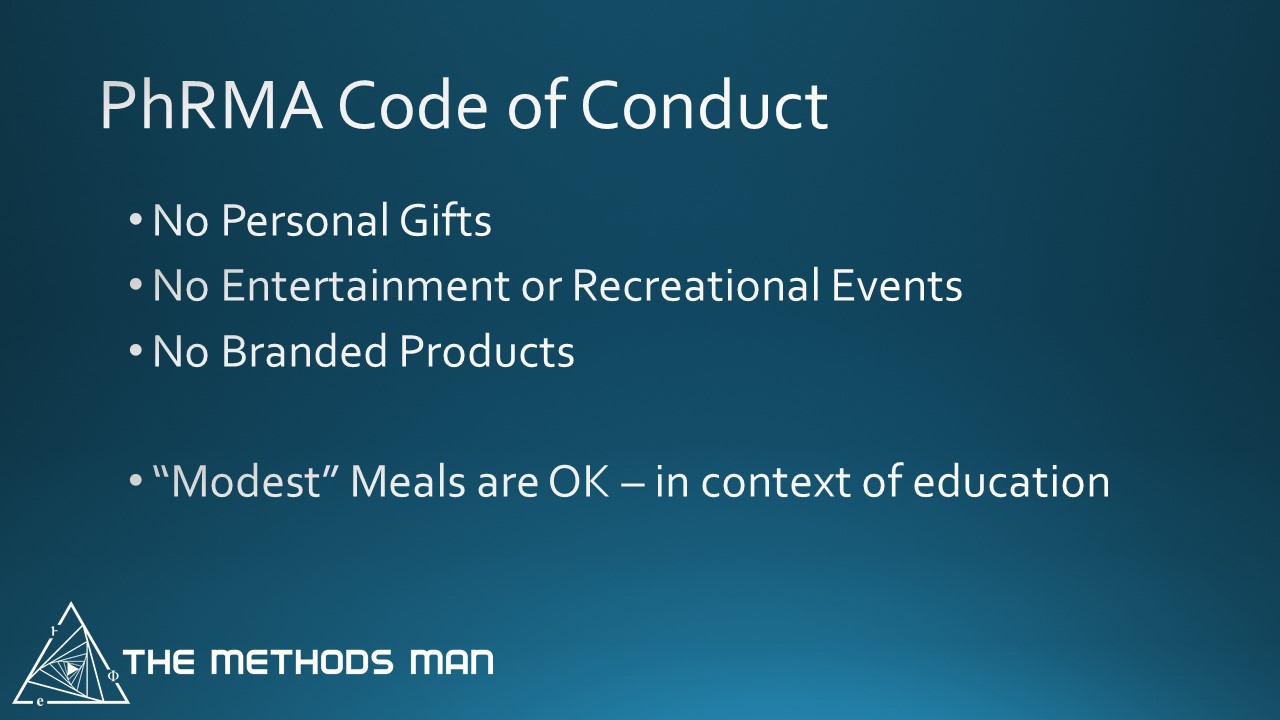

Here's the background. In 2002, Pharma companies signed onto a set of policies regarding the way they would interact with physicians, a code of conduct. Updated in 2009, this code has a few notable points in it:

Consider this the baseline rules of engagement. OK, a number of medical centers adopted their own, more strict, policies. These included limiting access of pharmaceutical reps to the facilities entirely, and strict punishments or fines for rule violations, among others.

The introduction of these strict policies provides a window to see how prescribing habits change. And they did change, a bit.

The researchers looked at the prescribing habits of 2,126 providers at 19 medical centers before and after these strict policies were introduced. Specifically, they looked at the prescription rate of drugs that were actively marketed – the technical term here is pharmaceutical “detailing”. This sounds relatively simple, but there are some important twists to be aware of.

Take a look at this graph.

The yellow line represents the rate of prescription of marketed drugs among physicians at medical centers that instituted strict code-of-conduct statutes. The blue line is a well-matched group of control physicians. The first important thing to notice is that the prescription rate for both groups declined over time.

But while the prescription rate of marketed drugs continued to drop in the medical centers with strict anti-marketing policies, the rate in control-physicians leveled off.

The overall decline in the prescription rate of marketed medications is likely due to the introduction of more generics. If you exclude the drugs that had a generic competitor, the difference between the two groups becomes even more stark:

Here you see essentially flat prescription rates until the medical centers instituted strict anti-marketing policies, after which a pretty significant decline occurs.

In short, the policies work.

Well – they work if you think that prescribing a promoted drug is inherently a bad thing. Just because a drug is marketed actively doesn’t mean it’s bad. The salient question is what percent of the time the marketed drug is the most cost-effective choice for the patient. If you think that’s a rare situation, then you should be all for policies that reduce the rate of these prescriptions.