Hydrocodone, the DEA, and Unintended Consequences

/A Michigan-based study suggests that opioid prescribing increased when hydrocodone was made harder to prescribe.

This week – post-operative opioids, and the unintended consequences that occur when well-intentioned government officials make seemingly reasonable policy decisions as we look at this article, appearing in JAMA Surgery.

Remember 2014? I miss that year.

Let’s go back to a simpler time: October of 2014. We’re in the height of the Ebola epidemic, Taylor Swift released “1989”, and no one knew what the “Internet Research Agency” was.

Also in October 2014, the DEA reclassified hydrocodone to schedule II from schedule III.

The opioid epidemic, which continues to ravage the country, was on the upswing and excessive prescription of narcotics was one of the commonly-blamed culprits. By moving hydrocodone from schedule III to schedule II, the DEA was hoping to curb its use.

The JAMA Surgery paper shows that just the opposite happened.

Researchers used insurance claims data from the Michigan Value Collaborative to identify around 22,000 patients who had undergone 1 of 19 common elective surgical procedures, mostly general surgery stuff with a fair amount of Ortho and Ob/Gyn.

They then looked to see what opioid prescriptions they filled post-operatively.

Prior to the schedule change, the average post-surgical patient filled a prescription for 371 oral morphine equivalents – about 74 5mg Vicodin tablets.

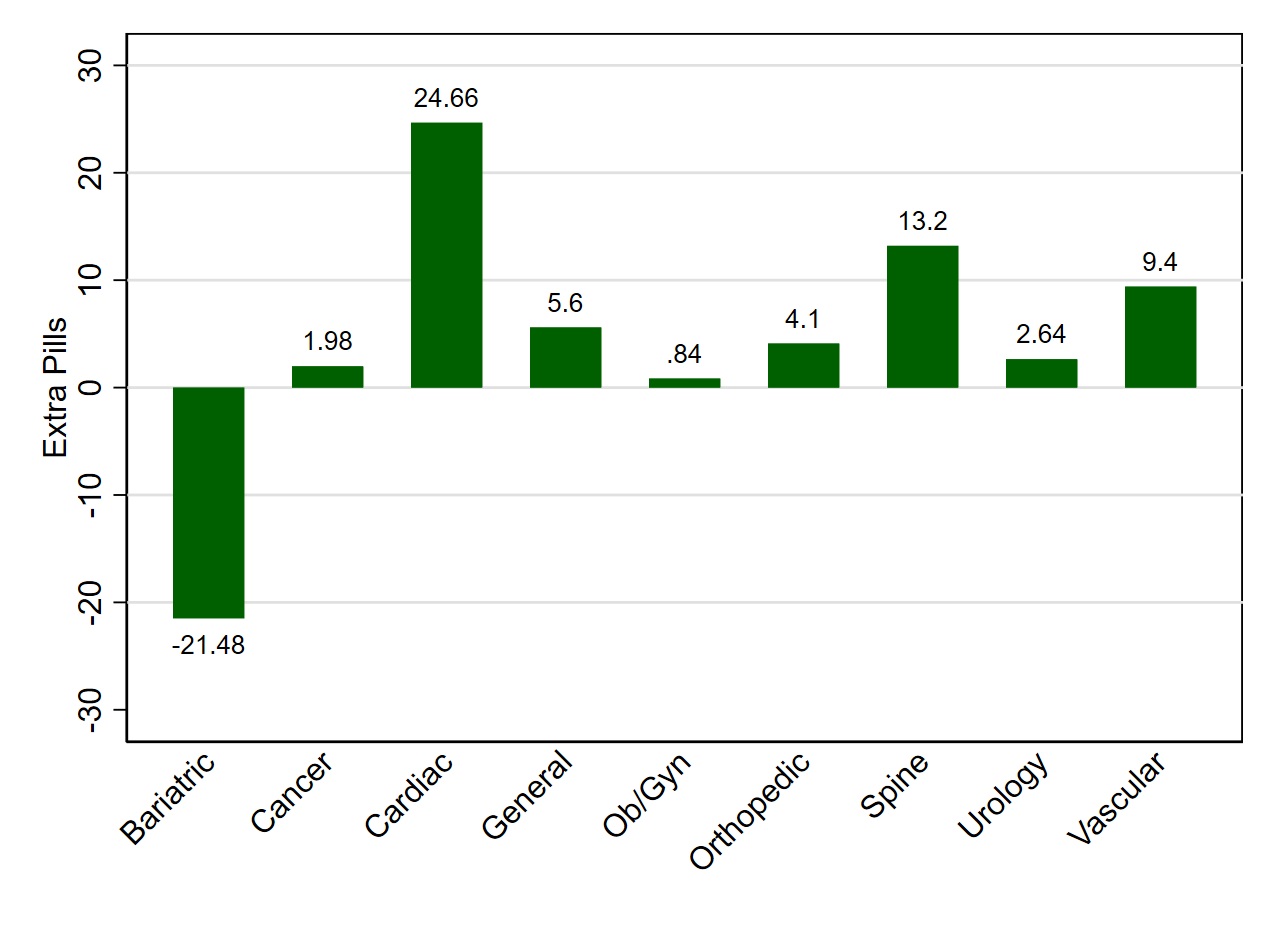

Pill count increase by surgery type after hydrocodone moved to schedule II from schedule 3

After the schedule change, when it would be more difficult to prescribe Vicodin, the average prescription increased by 7 tablets. This was across the board in surgical subtypes with the exception of bariatrics – spine surgeons prescribed 13 extra tablets after the change, cardiac surgeons 25 extra pills.

I, very much not a surgeon, was baffled, so I turned to my favorite surgeon, Niamey Wilson, to suss this one out for me.

Could it really be that all these extra pills are being prescribed because we can’t call them in any more? To be honest, this seems like the most likely answer, as a pretty extensive multivariable adjustment did not reveal any other explanations. In order to avoid the hassle of writing a new script, some docs are just increasing the initial amount given post-op. And this is a real problem, because excessive prescribing post-operatively may increase the potential for abuse and diversion.

OK a word of caution. This study only enrolled people who filled opioid prescriptions post-operatively. If the change in scheduling caused some physicians to abandon prescribing opioids altogether, we wouldn’t see that in this data which could seriously bias the results. But I think that is an unlikely interpretation.

No I think more likely this is a simple case of unintended consequences and a valuable reminder that sometimes a committee making decisions in Virginia might do well to talk to the boots on the ground first.