Weight Loss, Even Intentional Weight Loss, Associated with Cancer

/Losing weight is hard — success might signal that something else is wrong.

As anyone who has been through medical training will tell you, some little scenes just stick with you. I had been seeing a patient in our resident clinic in West Philly for a couple of years. She was in her mid-60s with diabetes and hypertension and a distant smoking history. She was overweight, and had been trying to improve her diet and lose weight since I started seeing her without much luck. One day she came in and was delighted to report she had finally started shedding some pounds – about 15 in the last two months.

I enthusiastically told my preceptor that my careful dietary counseling had finally done the job. She looked through the chart for a moment and said… yeah… is she up to date on her cancer screening? A workup revealed adenocarcinoma of the lung. She did well, actually, but the story… you know… stuck with me.

The textbooks call it “unintentional weight loss”, often in big scary letters and every doctor will go just a bit pale if a patient tells them that, despite efforts not to, they are losing weight.

But true unintentional weight loss is not really that common. After all, most of us are at least half-heartedly trying to lose weight all the time. Should doctors be worried when we are successful?

A new study suggests that, perhaps, they should.

We’re talking about this study, appearing in JAMA, which combined participants from two long-running observational cohorts: 120,000 women from the Nurses’ Health Study, and 50,000 men from the Health Professionals Follow-up Study. (These cohorts started in the 70s and 80s so we’ll give them a pass on the gender-specific study designs).

The rationale of enrolling healthcare providers in these cohort studies is that they would be reliable witnesses of their own health status. If a nurse or doctor says they have pancreatic cancer, it’s likely they truly have pancreatic cancer. Detailed health surveys were distributed to the participants every other year and the average follow-up was more than a decade.

Source: Wang et al. JAMA 2024.

Participants recorded their weight (as an aside, a nested study found that self-reported rate was extremely well-correlated with professionally-measured weight), and whether they had received a cancer diagnosis since the last survey.

This allowed researchers to look at the phenomenon I had described above. Would weight loss precede a new diagnosis of cancer? And – more interestingly – would intentional weight loss precede a new diagnosis of cancer.

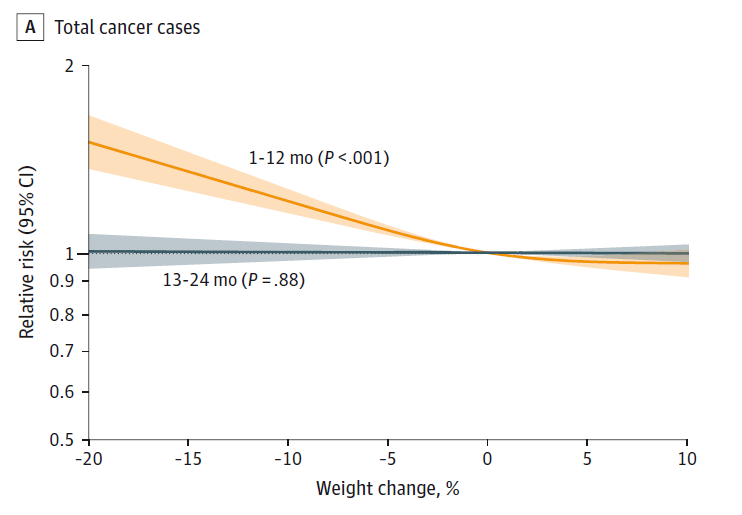

I don’t think it will surprise you to hear that individuals in the highest category of weight loss – those who lost more than 10% of their body weight over a two-year period had a larger risk of being diagnosed with cancer in the next year – that’s the yellow line in this graph - In fact, they had about a 40% higher risk than those who did not lose weight.

Source: Wang et al. Jama 2024

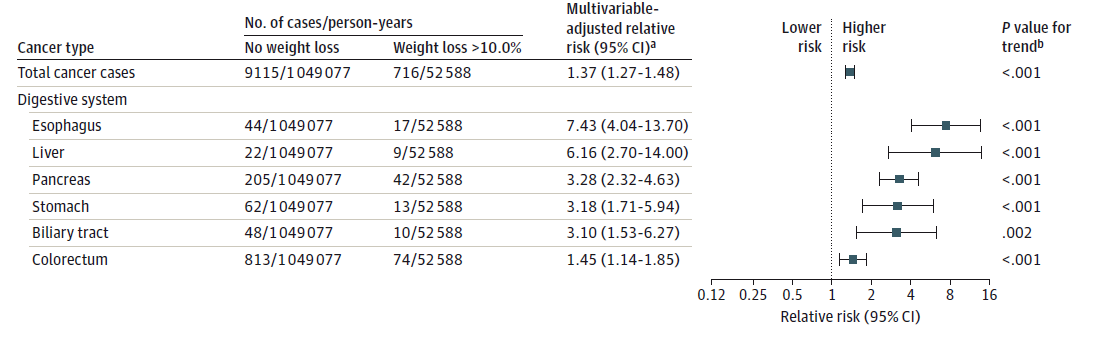

This risk was found across multiple cancer types, though cancers of the GI tract, not surprisingly, were most strongly associated with antecedent weight loss.

Source: Wang et al. JAMA 2024

Ok – what about intentionality of weight loss? Unfortunately, the surveys did not ask “are you trying to lose weight”. Rather, the surveys asked about exercise and dietary habits. The researchers leveraged these answers to create three categories of individuals. Those who seemed to be trying to lose weight – defined as people who had increased their exercise and dietary quality. Those who didn’t seem to be trying to lose weight – they changed neither exercise nor dietary behaviors. And a middle group that changed one or the other behaviors but not both.

Let’s look, then, at those people who really seemed to be trying to lose weight. Over two years, they got more exercise and improved their diet.

If they succeeded – losing 10% or more of their body weight - they still had a higher risk of cancer than those who had not lost weight. About 30% higher – not that different from the 40% increased risk when you include those folks who weren’t changing their lifestyle.

Source: Wang et al. JAMA 2024

This is really why this study is important. The classic teaching is that unintentional weight loss is a bad thing and needs a workup. That’s fine. But we live in a world where perhaps the majority of people are, at any given time, trying to lose weight. The truth is that losing weight with ONLY lifestyle modifications – exercise and diet – is actually really hard. So “success” there might be a sign that something else is going on.

But we need to be careful here. I am not by any means trying to say that people who have successfully lost weight have cancer. Both of the following statements can be true:

Significant weight loss, whether intentional or not, is associated with a higher risk of cancer.

And

Most people with significant weight loss will NOT have cancer. Both of these can be true because cancer is, fortunately, rare. Of people who lose weight, the vast majority will lose weight because they are engaging in healthier behaviors. Some small number may lose weight because something else is wrong. It’s just hard to tell the two apart.

Out of the nearly 200,000 people in this study, only around 16,000 developed cancer during follow-up. Again, while your chance of having cancer is slightly higher if you’ve experienced weight loss, the chance is still very low.

The other thing we need to be careful about is to say that weight loss does not CAUSE cancer. The idea here is that some people are losing weight because of an existing cancer and its various metabolic effects that has not yet been diagnosed. This is sort of borne out if you look at the risk of being diagnosed with cancer as you move farther away from the interval of weight loss.

Source: Wang et al. JAMA 2024

The farther you get from the year of that 10% weight loss, the less likely you are to be diagnosed with cancer. Most of these cancers are diagnosed within a year of the weight loss. In other words, if you’re seeing this and getting worried that you lost weight 10 years ago – you’re probably out of the woods. That was, most likely, just you getting healthier.

Last thing – we have methods for weight loss now that are WAY more effective than diet or exercise – I’m looking at you Ozempic. But even aside from the weight loss wonder drugs, there are surgery and other interventions. This study did not capture any of that data. I mean, Ozempic wasn’t even on the market during this study – so we can’t say anything about the relationship between weight loss and cancer among people using non-lifestyle mechanisms to lose weight.

It's a complicated system. But the clinically actionable thing here is to notice if patient’s have lost weight. If they’ve lost it without trying – further workup is reasonable. If they lost it but were trying to lose it? Tell them good job. And consider a workup anyway.

A version of this commentary first appeared on Medscape.com.