Are We Doing Enough to Stop Bullying?

/A new study reminds us that preventing bullying may truly save lives.

If you have kids of a certain age, this won’t come as a surprise to you. But kids across the country are suffering.

Mental health among teen girls is the worst it has been since measurement began, with the 2021 Youth Risk Behavior survey showing that 3 out of 5 teen girls feel persistent sadness and one out of three have seriously considered attempting suicide.

The numbers are even worse among kids who identify as sexual and gender minorities – with half of LGBTQ+ teens in that same survey reporting seriously considering suicide.

The causes of this epidemic of youth depression are not entirely clear, though fingers have, appropriately in my opinion, pointed to social media and the pandemic as contributors to the shocking numbers.

Whatever the cause, it’s clear that something needs to be done. And amid the myriad of proposals percolating through congress from banning TikTok to increasing the age limit for social media use, there may be some lower hanging fruit to pick: stopping bullying.

I’m focusing on bullying this week, thanks to this research letter appearing in JAMA Pediatrics which shows a fairly strong effect of anti-bullying legislation on suicidal thoughts, plans, and attempts among LGBTQ+ youth.

Source: JAMA Pediatrics

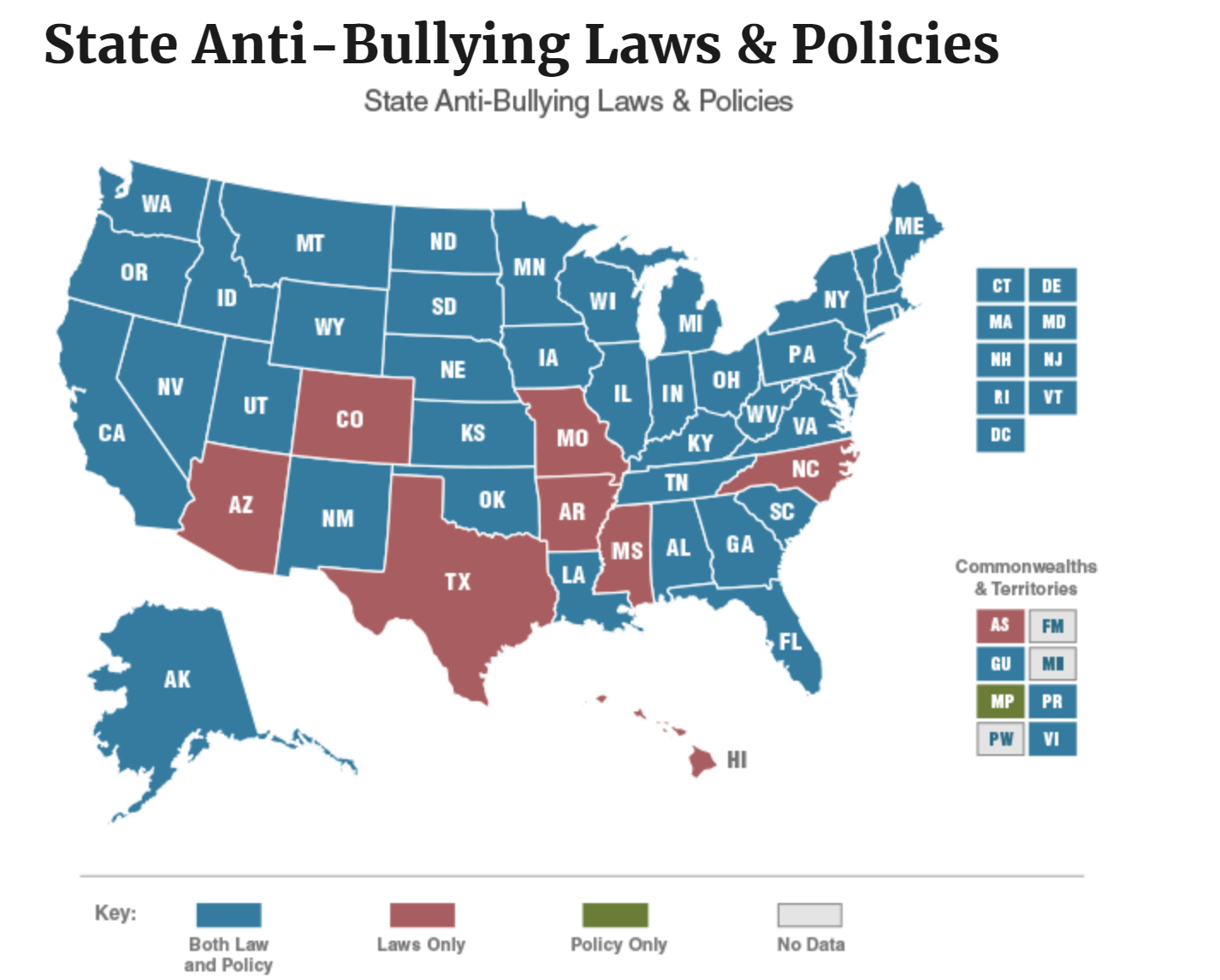

Here’s the state of play. The first anti-bullying law was passed in 1999 in Georgia. Since then, every state in the country has enacted some type of anti-bullying legislation, and many have formalized anti-bullying policies.

Source: stopbullying.gov

Now, these laws vary widely: some explicitly define bullying, some don’t. Some mandate how bullying incidents are investigated, some don’t. Some mandate reporting and what consequences need to be imposed on bullies, and some don’t. But… it’s something. Did it make a difference?

Researchers led by Joseph Sabia at San Diego state leveraged the fact that the Youth Risk and Behavior Survey is repeated every year – albeit on different kids. Given that, and the fact that different states enacted their anti-bullying laws at different times, they could look at the change in suicidal ideation and behaviors before and after the laws were introduced.

The results are fairly impressive. For example, you can see that compared to the year prior to legislation, there was a significant decrease in suicide attempts among LGBTQ+ youth in the subsequent years. The authors show similar results for suicidal ideation and plans as well.

The results were fairly consistent across various sexual and gender orientations. Youth who identified as gay or lesbian had a 65% reduction in the odds of suicidal thoughts after anti-bullying legislation was enacted, and a 40% reduction in the odds of suicide planning. Students unsure of their gender or sexual orientation had a 50% reduction in the odds of attempted suicide. The only subgroup that was not associated with a benefit from anti-bullying legislation were students who identified as bisexual.

Of course, these laws are not enacted in a vacuum – we can’t really draw a causal line from the laws to less suicide. It’s likely that along with these laws, other cultural and societal shifts may occur that are protective. And of course, every state has these laws on the books now – so to some extent this step has been taken. But we should probably look at this study as a call to examine how we handle bullying more broadly, and to be a reminder of the toll it can take both inside – and outside – of the classroom. Remember that cyberbullying is rampant and often invisible to parents and teachers.

I should note that the data from this study predates the pandemic. The rise of depression in teens broadly in the past several years may have nothing to do with bullying. But its certain that, amid all the stresses teens are facing, from the pressure to fit in, the unrealistic standards they see on social media, and the social isolation of the pandemic, that bullying may, for some, be the final straw.

A version of this commentary first appeared on Medscape.com.