Fluvoxamine for COVID-19: A New Weapon in the Fight?

/The antidepressant appears to have some ability to prevent worsening in outpatients with COVID-19.

By virtually all metrics, vaccine development for COVID-19 has been an astonishing success. But when it comes to therapeutics, the picture is much more mixed. This means the tip of the spear of the battle against coronavirus is and will remain vaccination, but, as you know, not everyone is getting vaccinated. We need therapeutics.

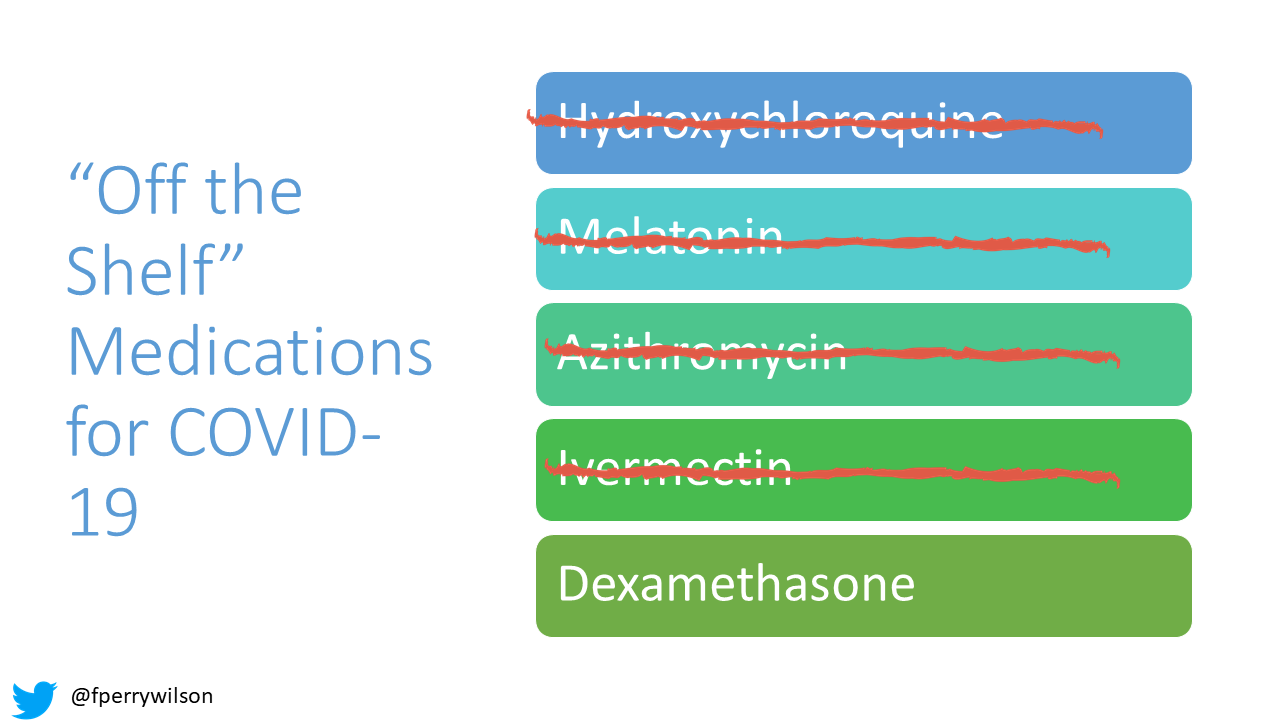

For nearly two years, the search for existing molecules with activity against COVID-19 has proceeded apace, but the process has been haphazard, and colored by political bias and misinformation. Melatonin, hydroxychloroquine, azithromycin, and most recently ivermectin showed some initial promise only for rigorous randomized trials to shoot them down.

The idea that some existing drug would be a miracle cure for COVID-19 is basically fantasy. As Dr. Matsumoto said in the 1990 post-apocalyptic action film Robot Jox “That Kind of Luck Does Not Exist”.

But the idea that some existing molecule might have some efficacy, some moderate ability to curb the disease process is much more likely. See dexamethasone – a drug that costs about $1 a pill – for an example of this. Does it save every life? No. But it has clearly moved the needle on COVID-19 care.

And an old drug may be joining our COVID arsenal. A new, large clinical trial suggests that fluvoxamine – yes the antidepressant fluvoxamine – might substantially reduce the severity of COVID-19 illness.

But before we dig into the clinical results, it’s important to consider whether there is even biologic plausibility here. Why should fluvoxamine work against COVID?

Fluvoxamine

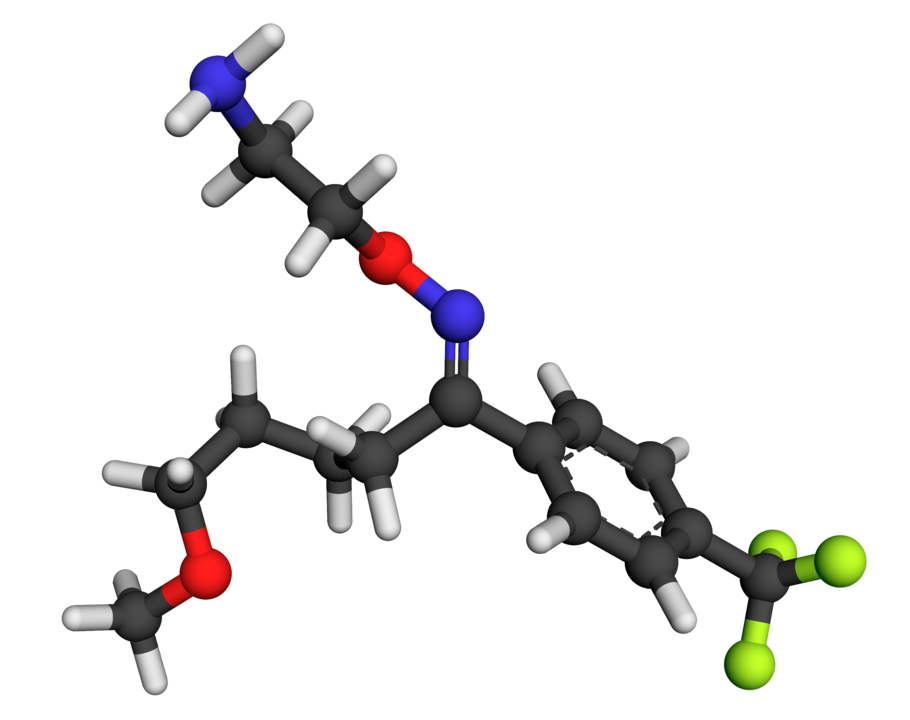

This is the molecule itself.

It’s a potent binder of the serotonin transporter, leading to its anti-depressant effects, but this doesn’t explain any anti-COVID activity.

The off-target effects of fluvoxamine are more interesting. Of all the SSRIs, fluvoxamine has the strongest affinity for the sigma-1 receptor – which might lend it some of its anxiolytic effects. But that receptor has many effects. This 2019 Science and Translational Medicine article suggests the receptor may have a substantial role in cytokine release, which is of course a mechanism by which COVID-19 lands people in the hospital.

SSRIs also have well-described platelet-inhibiting properties, and the pro-thrombotic nature of COVID-19 is equally well-described.

So there is some potential there there. But as I’ve said over and over again in this space, biologic plausibility is the start of medical research, not the end.

You need real, randomized data to move from “interesting drug” to “new treatment for COVID”.

In November of 2020, the first such data came out in JAMA. 152 outpatients with COVID-19 were randomized to 100 mg of fluvoxamine 3 times a day for 15 days or placebo.

None of the patients in the fluvoxamine group had clinical deterioration, compared to 6 in the placebo group – a significant difference, but the small numbers here leave plenty of room for interpretation.

Now we have a much more definitive trial – thanks to the TOGETHER consortium, which uses an adaptive design with a standardized protocol to rapidly evaluate potential new therapies. This is the same group that recently poured cold water on Ivermectin, as their data showed no statistical difference in outcomes among individuals randomized to ivermectin versus placebo.

But swap out ivermectin with fluvoxamine, and the results were different. Now, this data has not yet been peer-reviewed, but this appears to be a high-quality study – with a pre-registered endpoint and a decent sample size of 1,472 outpatients with COVID-19. Half of them were randomized to receive 100mg of fluvoxamine twice daily for 10 days, the rest got placebo.

The primary outcome was a composite of hospitalization or an ED visit for observation that lasted longer than 6 hours.

The medication did indeed reduce the risk of that primary endpoint – something none of the other candidates in TOGETHER trials have done yet – with 10.4% of the fluvoxamine group compared to 14.7% of the placebo group getting hospitalized or spending time in the ED.

That means you’d need to treat around 23 patients with fluvoxamine to avoid one patient clinically decompensating. At about fifty cents a pill, or $10 for a course of this therapy, that’s not a bad deal. Regeneron’s monoclonal antibody cocktail is about $1000 for a dose.

Harder endpoints didn’t differ significantly between the groups. 2.3% of the fluvoxamine group died compared to 3.3% of the placebo group but that difference, while encouraging, is consistent with a chance finding.

Indeed, the success of the drug was driven primarily by the fact that fewer fluvoxamine patients had a prolonged stay in the ED – the difference in hospitalization full stop was not as profound.

Other limitations: The study was conducted entirely in Brazil, where vaccination rates are low, and largely prior to the dominance of the delta variant – so interpret these results with caution.

Also I feel obliged to remind everyone that fluvoxamine is not an entirely benign drug. Like all SSRIs, side effects include gastrointestinal problems, weight gain, and sexual dysfunction.

Still, this is how this stuff is SUPPOSED to work. You start with some biologic plausibility, do some proof of concept studies, confirm with a large randomized trial. Ideally, you follow that up with a validation trial. You don’t just pick a drug with biologic plausibility and start selling it off label online and promoting it on YouTube and Twitter. This is a case-study for why. It muddies the waters. There is a process to vet potential therapies – and fluvoxamine shows us how the process should work.

Is fluvoxamine a game changer? No. As I said at the beginning, we are incredibly unlikely to find a medication off-the-shelf that just so happens to cure COVID-19. But it may provide some real benefit at a reasonable cost. So let’s keep going down this road, evaluate the effect of this drug in a broader population, in the face of Delta, and even in hospitalized patients, and use our most rigorous standards to figure out the truth.

A version of this commentary first appeared on medscape.com.