When To Exercise if You Want to Live Longer

/A new study suggests that “Weekend Warriors” survive just as long as more regular exercisers.

150 minutes a week. That’s the minimum recommended amount of moderate-intensity exercise the federal government advises the American people to do to optimize their health.

150 minutes a week. That number wasn’t pulled out of thin air. There is a bunch of observational data that shows that people who are more physically active have better health outcomes. Those who hit that 150 minute-a-week mark have around a 30% reduction in overall mortality rates, even when you control for health status at baseline.

But only about half of Americans actually get that much exercise, as you can see here, with younger people doing better than older people, and men getting a bit more exercise than women.

How do you get more people to exercise? Maybe you need to make it easier.

Part of the reason a lot of people miss the exercise target is that 150 minutes just seems daunting. The physical activity guidelines suggest that these 150 minutes be “spread throughout the week”. But not all of us have 30 minutes a day, Monday through Friday to take a brisk walk on a treadmill, or a jog around the block.

Could it be good enough to hit the weekly target all at once?

The agreed-upon scientific term for this behavior – doing all your weekly exercise in one or two big sessions - is the “Weekend Warrior” pattern. And, in this week’s JAMA Internal Medicine, a large study asks whether Weekend Warriors are as protected from death as people who spread their exercise more evenly.

The study leverages more than 350,000 responses to the US National Health Interview Survey – which is representative of the population at large. The researchers, led by Yafeng Wang, merged that survey data with the National Death Index, which captures date and cause of death for all deaths in the US.

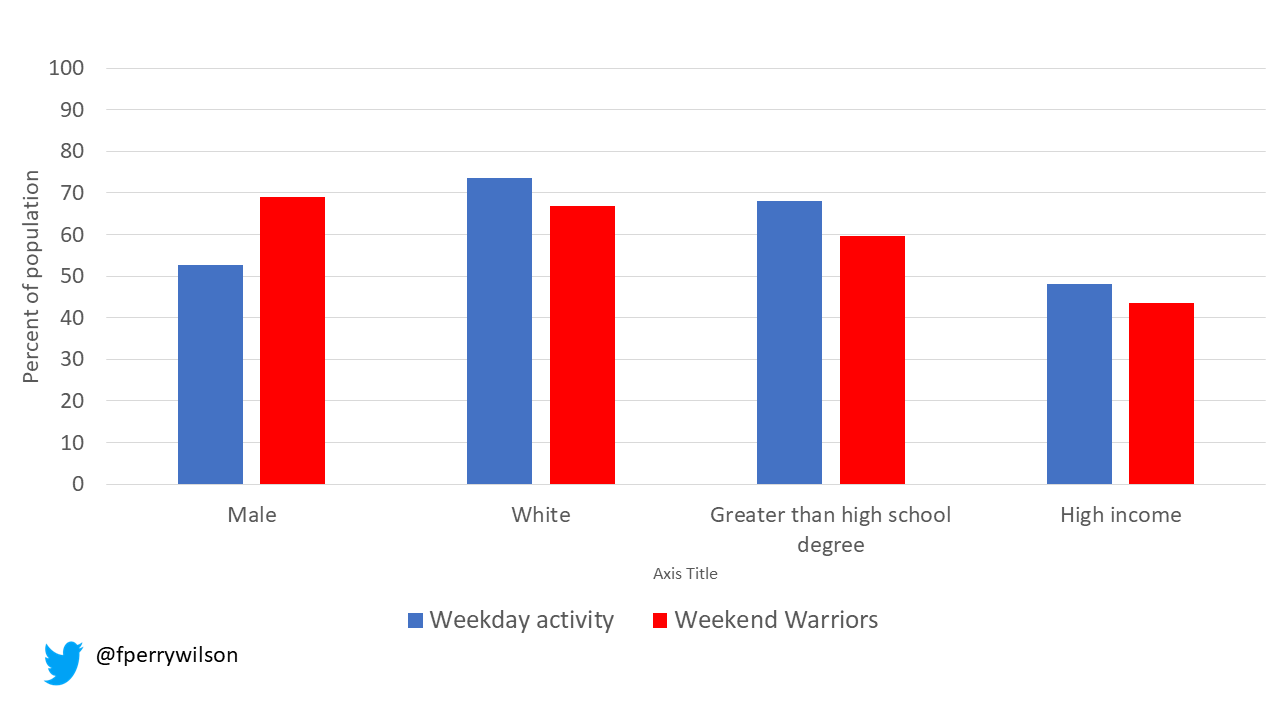

What do weekend warriors look like?

In the JAMA-IM study, compared to those who exercise regularly throughout the week, weekend warriors were younger, more likely to be male, less likely to be white, have a lower level of education and a lower overall income level. I think this speaks a bit to the idea that the ability to have 30 minutes a day to exercise is a marker of privilege. Not everyone has jobs with that kind of schedule, or the childcare to allow 30 minutes of “me time”.

So – topline results.

Overall, the researchers found that, compared to people who do not hit those 150 minutes a week of physical activity, those who do are significantly less likely to die – about 15% less likely. They had 23% less cardiovascular death and 12% less cancer death as well.

The duration of each exercise session seemed to matter a bit. Which is to say that the mortality benefit was seen in people who exercised more than 20 minutes at a time. Gotta get that heart rate up I guess.

So would those Weekend Warriors – cramming all their 150 minutes into 1 or 2 days – fare the best of all? Not really. The authors compared the Weekend Warriors to the Regularly Active and found no statistical difference in mortality rates. The conclusion? Yeah, the weekend exercise is probably good enough, but not better than a more spread out pattern.

Now, these studies are not as simple as they might seem at first blush. Individuals who are sick with chronic disease may exercise less because of that disease, and also be more likely to die because of that disease. That would make exercise appear protective, when in reality the ability to exercise is just a marker of general good health.

To avoid this reverse causation, the authors excluded individuals who had been diagnosed with cancer, bronchitis, COPD, or stroke at baseline. What’s more, they excluded deaths that occurred within 2 years of the survey being taken – on the idea that maybe an undiagnosed disease was already present and limiting exercise ability. This is smart epidemiology.

Of course, many things impact your ability to exercise and might make you live longer. A big one? Money. It is no secret that, in the US at least, having a high income is associated with better health outcomes. High-earners may also be able to afford that gym membership, or the babysitter to watch the kids while they get some exercise.

To address this confounder, and others that might spuriously link exercise and death, the results I’ve shown you were adjusted for income, age, sex, race, ethnicity, marital status, educational attainment, smoking, alcohol intake, other comorbidities, mobility, and self-rated health.

But statistical adjustment is a double-edged sword. While we want to adjust for things, like income, that are related to our exposure (exercise) and outcome (death), we do NOT want to adjust for things that lie along the causal pathway from exposure to outcome.

Take body mass index for example. At first blush, you might think we should adjust for BMI when evaluating the link between exercise and death. People with higher BMI may be able to exercise less and, in general, have worse health outcomes. That’s classic confounding.

But exercise may reduce BMI. In fact, one of the reasons exercise might be beneficial is because it reduces BMI. If we adjust for something along the causal pathway, we reach the wrong conclusion. This is why a strategy of “adjust for everything” is a really bad one.

The authors seem to recognize this, leaving BMI out of their primary analysis, but including an adjustment for BMI in a sensitivity analysis.

But the lesson of BMI might apply to some of the factors they adjusted for in the primary analysis too. Might exercise actually decrease smoking rates? Or alcohol intake? If so, these might be on that causal pathway from exercise to survival – not something we’d want to adjust for.

So we need to look at that final estimate of benefit – 15% reduction in mortality – with a bit of a skeptical eye. The true number could be quite a bit higher. It could probably be lower too.

Of course, physical activity, as a medical intervention, has just about the best risk : benefit ratio you could imagine. The message of this paper, underneath all the epidemiology and statistics is a simple one – get some exercise, whenever you can. It’s good for you.

A version of this commentary first appeared on Medscape.com.