The Cost and Benefit of Genetic Testing EVERYONE

/Screening every 30-year-old for three genetic conditions may be cost-effective.

Milestone birthdays are always memorable. Those ages when your life seems to fundamentally change somehow. Age 16 – a license to drive. Age 18 – you can vote to determine your own future and serve in the military. At 21, three years after adulthood, you are finally allowed to drink alcohol for some reason. And then… nothing much happens. At least until you turn 65 and become eligible for Medicare.

But imagine a future where turning 30 might be the biggest milestone birthday of all. Imagine a future, where at 30 – you get your genome sequenced – and doctors tell you what needs to be done to save your life.

That future may not be far off, as a new study shows us that screening every single 30-year-old in the US for three particular genetic conditions may not only save lives, but be reasonably cost-effective.

Getting your genome sequenced is a double-edged sword. Of course, there is the potential for substantial benefit – finding certain mutations allows for definitive therapy before it’s too late. That said, there are genetic diseases without a cure and without a treatment. Knowing about that destiny may do more harm than good.

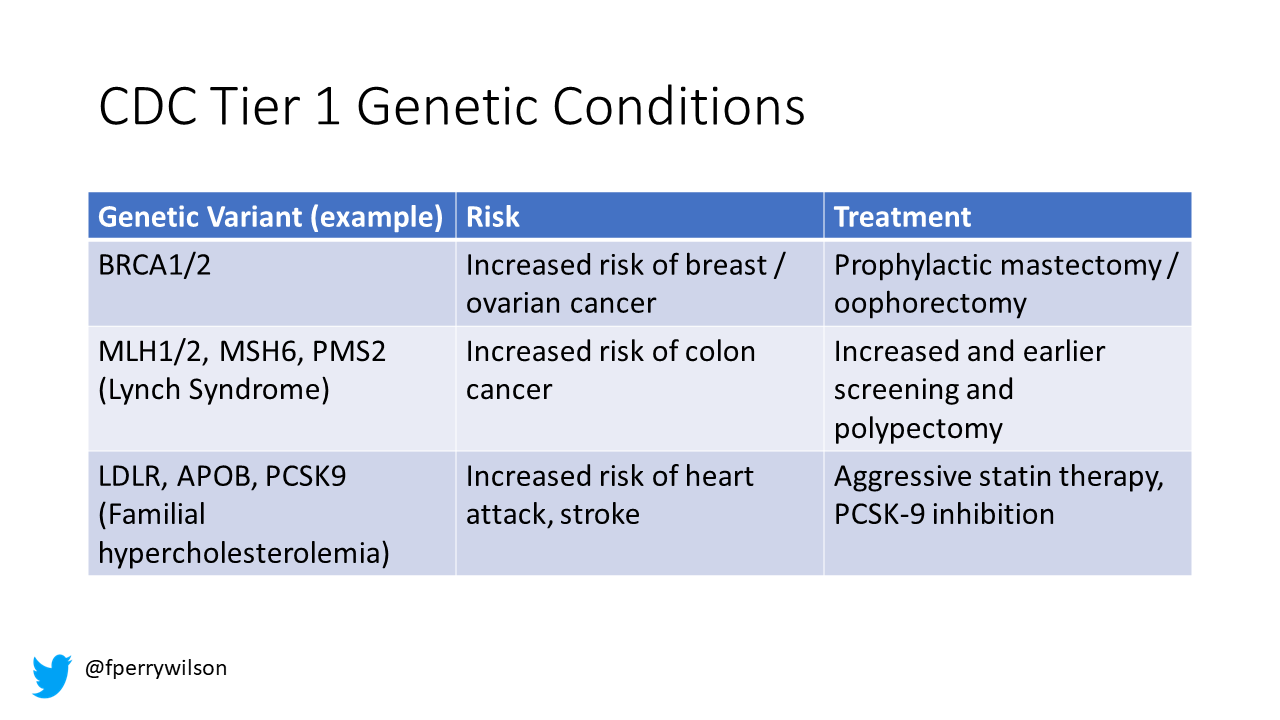

There are three genetic conditions described by the CDC as “Tier 1” conditions. Genetic syndromes with a significant impact on life-expectancy that also have definitive, effective therapies.

These include mutations like BRCA-1 and 2 associated with a high risk of breast and ovarian cancer, mutations associated with Lynch syndrome which confers an elevated risk of colon cancer, and mutations associated with familial hypercholesterolemia, which confer elevated risk of cardiovascular events.

In each of these cases, there is clear evidence that early intervention can save lives. Individuals at high risk of breast and ovarian cancer can get prophylactic mastectomy and salpingo-oophorectomy. Those with Lynch syndrome can get more frequent screening for colon cancer and polypectomy, and those with familial hypercholesterolemia can get aggressive lipid lowering therapy.

I think most of us would probably want to know if we had one of these conditions – most of us would use that information to take concrete steps to decrease our risk. But just because a rational person would choose to do something doesn’t mean it’s feasible. After all, we’re talking about tests and treatments that have significant costs.

This week, appearing in the Annals of Internal Medicine, Doctors Josh Peterson and David Veenstra present a detailed accounting of the cost and benefit of a hypothetical nationwide, universal screening program for tier 1 conditions. And, in the end, it may actually be worth it.

Source: Annals of Internal Medicine

Cost-Benefit analyses work by comparing two independent policy choices – the status quo – in this case a world in which some people get testing for these conditions, but generally only if they are at high risk based on strong family history, and an alternative policy – in this case universal screening for these conditions starting at some age.

Source: Annals of Internal Medicine

After that, it’s time to play the assumption game. Using the best available data, the authors have to decide things like what percent of the population will have each condition, what percent of those individuals will actually act on the information definitively, and how effective those actions would be if taken.

As an example, the authors assume that the prevalence of mutations leading to a high risk of breast and ovarian cancer is around 0.7%, and that up to 40% of individuals who learn they have one of these mutations would get prophylactic mastectomy, which would reduce the risk of breast cancer by around 94%. (I ran these numbers past my wife, a breast surgical oncologist, who agreed these seemed reasonable).

Assumptions in place, it’s time to add costs. The cost of the screening test itself, of course – the authors use $250 as their average per-person cost. But also the cost of treatment – around $22,000 per person for a bilateral prophylactic mastectomy – or the cost of statin therapy for those with familial hypercholesterolemia, or all those colonoscopies for those with Lynch syndrome.

Finally, an assessment of quality of life. Obviously, living longer is generally considered better than living shorter, but marginal increases in life expectancy at the cost of quality of life might not be a rational choice.

You then churn these assumptions through a computer, and see what comes out. How many dollars does it take to save one quality-adjusted life year. I’ll tell you right now that $50,000 per QALY used to be the unofficial standard for a “cost-effective” intervention in the US. Researchers have more recently used $100,000 as that threshold.

Let’s look at some hard numbers.

If you screened 100,000 30-year olds, 1500 would get news that something in their genetics was, more or less, a ticking time bomb. Some would choose to get definitive treatment and the authors estimate that the strategy would prevent 85 cases of cancer. You’d prevent 9 heart attacks and 5 strokes by lowering cholesterol levels among those with familial hypercholesterolemia. Obviously, these aren’t huge numbers, but of course most people don’t have these hereditary risk factors. For your average 30 year-old, their genetic screening test will be completely uneventful, but for those 1500 it will be life-changing, and potentially life-saving.

But is it worth it? The authors estimate that, at the midpoint of all their assumptions, the cost of this program would be $68,000 per quality-adjusted life-year saved.

Of course that depends on all those assumptions we talked about. Intertestingly, the single factor that changes the cost effectiveness the most in this analysis is the cost of the genetic test itself – which I guess makes sense consider we’d be talking about testing a huge segment of the population. If the test cost $100, instead of $250, the cost per quality-adjusted life year would be $39,700 – that is well within the range that most policymakers would support. And given the rate at which the cost of genetic testing is decreasing, and the obvious economies of scale here, I think $100 a test is totally feasible.

The future will bring other changes as well. Right now, there are only 3 hereditary conditions designated as Tier 1 by the CDC. If conditions are added, that might also swing the calculation more heavily towards benefit.

This will represent a stark change from how we think about genetic testing currently – focusing on those whose pre-test probability of an abnormal result is high due to family history or other risk factors. But, for the twenty-year olds who are reading this, I wouldn’t be surprised if your 30th birthday is a bit more significant than you have been anticipating.

A version of this commentary first appeared on Medscape.com.