The Problem With Ultra-Processed Foods? They're Delicious.

/A new study suggests that the problem with ultra-processed foods isn’t that they contain horrible fattening chemicals. It’s that we eat too much of them.

Processed foods. Wait. Ultra-processed foods. Before this week I wasn’t entirely sure what ultra-processed food even is. Like – pills? Pills that you swallow and that’s all the nutrition you need.

(Publishers, call me).

No, ultra-processed foods are “cheap industrial sources of dietary energy and nutrients plus additives… and containing minimal whole foods”. So, like Cheetos. Delicious!

And whether you are a fan of the Mediterranean diet, the keto diet, the paleo diet, or my personal favorite the “alcohol and salads” diet, you are probably avoiding ultra-processed foods. Observational data would suggest that you are right – multiple studies have demonstrated that high intake of ultraprocessed foods increase the risk of obesity, diabetes, and even death.

But until now we didn’t have a good sense of causality. Maybe people who eat ultraprocessed foods have other problems that we are failing to capture. Differences in socioeconomic status alone could drive much of the observational associations seen.

Now we have a rigorously conducted study appearing in Cell Metabolism of the impact of ultraprocessed foods and the results are fascinating.

I mean, I get it.

Twenty volunteers were placed into a metabolic lab for 4 weeks. There, all their meals and snacks were provided for them. For a two-week period (chosen at random) they would get an ultra-processed diet. The other two weeks, they would get an unprocessed diet. Here’s a comparison of a typical lunch in the two diet groups:

Now, everyone was given roughly twice the amount of calories they needed to stay in energy balance and told simply to eat at will – eat what they want. The dieticians had their work cut out for them, but they matched the presented food in terms of calorie content, macronutrient content, salt, and even energy density.

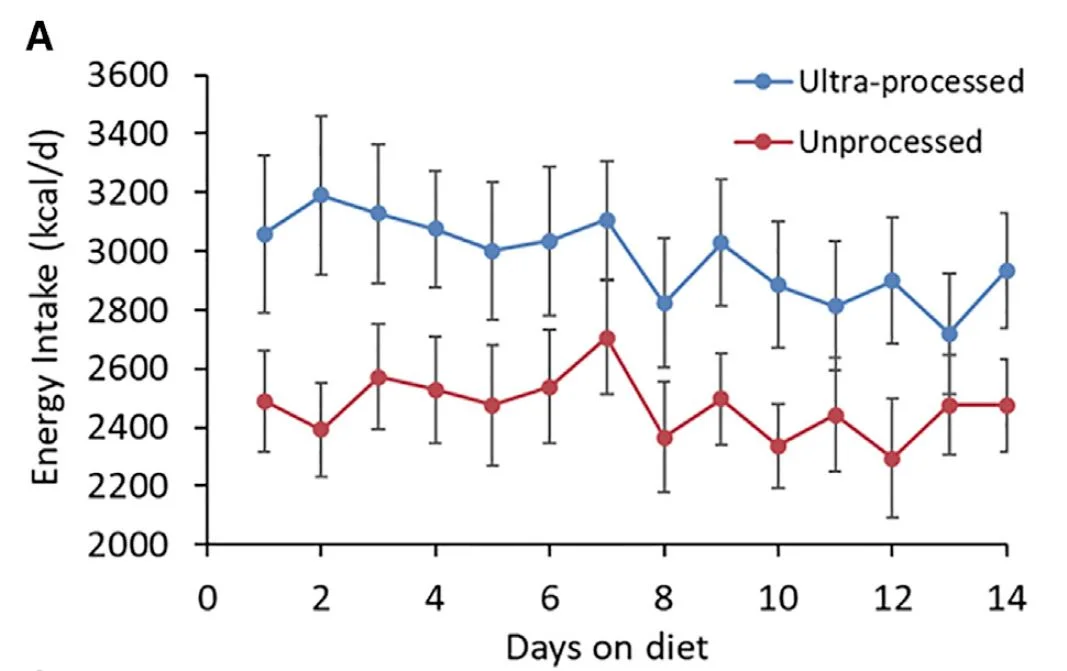

With the options on the table, participants ate.

To be fair, 500 calories is like one package of Twinkies, so…

And in the case of ultra-processed food, they ate some more.

On average, around 500 Calories a day more then they did when presented with an unprocessed diet.

Most of the overeating occurred during breakfast and lunch, not dinner or snacking, which surprised me a bit as those processed snacks look particularly delicious.

Is there an “unappealing food” diet? Patent pending.

And all those extra calories added up. On average, participants gained about a kilogram on the ultraprocessed diet and lost about a kilogram on the unprocessed diet, regardless of which order they were randomized.

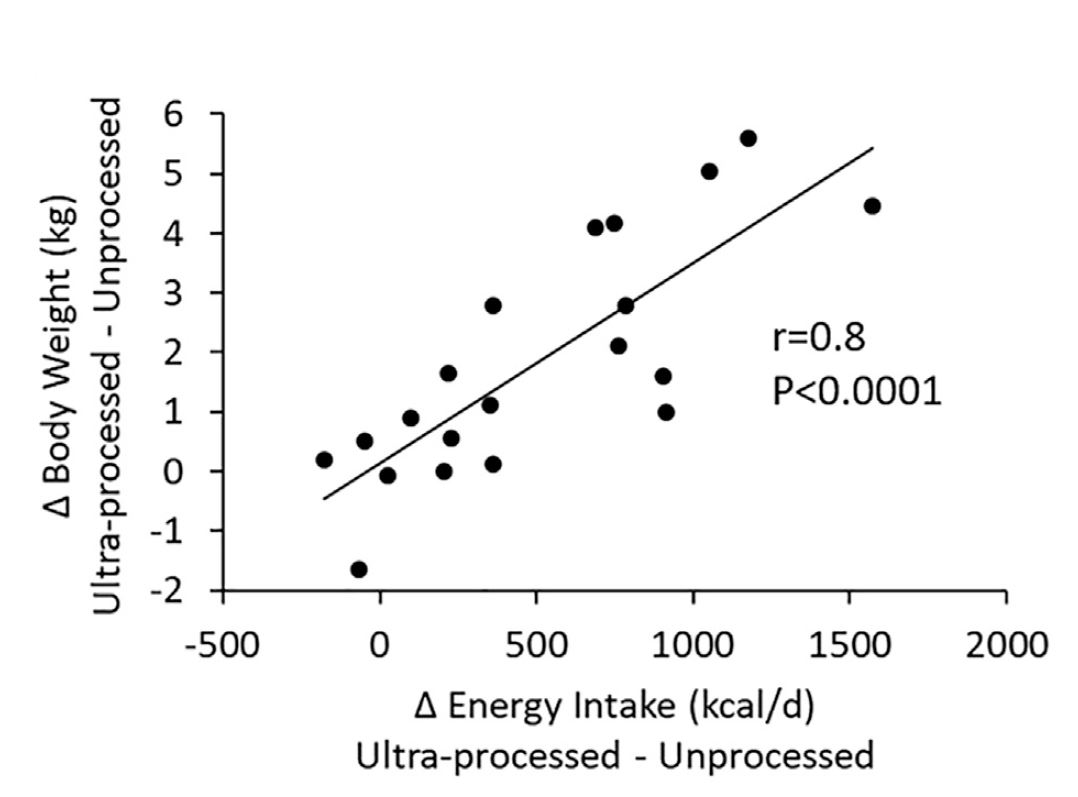

Now, it would be easy to look at this study and get on the anti-processed-foods bandwagon, but I want to point something out. The reason people gained weight on the ultra-processed diet was because they ate more calories. Here’s a scatterplot of the relationship between weight gain and calorie intake.

Calories in, Calories out. Come at me, bro.

In other words, this study does not show that ultraprocessed foods are toxic, or imbued with evil humours or lead to more weight-gain-per-calorie. It doesn’t show that large corporations are adding special fattening chemicals to their food products.

It shows, mostly, that ultra-processed foods taste better – or are easier to eat – or have more “cravability” a word a close friend of mine recently introduced me to. Most likely, this is why they are “bad” for us – through feats of science and engineering, corporations have created foods that smack us right in the pleasure centers of the brain, and we continue to eat them even after we shouldn’t. Maybe this is one of those things that if we simply acknowledge, we can avoid?

Or maybe not. This whole commentary is making me hungry.

This commentary first appeared on medscape.com.