Sleep Deprivation Increases After-Dinner Snacking, Weight Gain

/Sleep deprivation leads to more after-dinner snacking and weight gain, according to a study in Current Biology.

And I, like you, should probably be getting more sleep. This realization came after reading this study appearing in Current Biology – a Cell publication – that examined, in great detail, just what happens metabolically when an individual is sleep deprived.

Even more interesting, they examined whether “catch up sleep” – that stuff we try to get on the weekend – makes any difference. This is a super interesting study which shows that the internal banker keeping track of your sleep debt is not satisfied when he is paid back only on Saturday and Sunday.

Interestingly, this is all I remember about the periodic table as well.

36 healthy volunteers were brought into a closed unit for 2 weeks. For three days, they were each in bed for 9 hours – affording them the opportunity for a good night sleep.

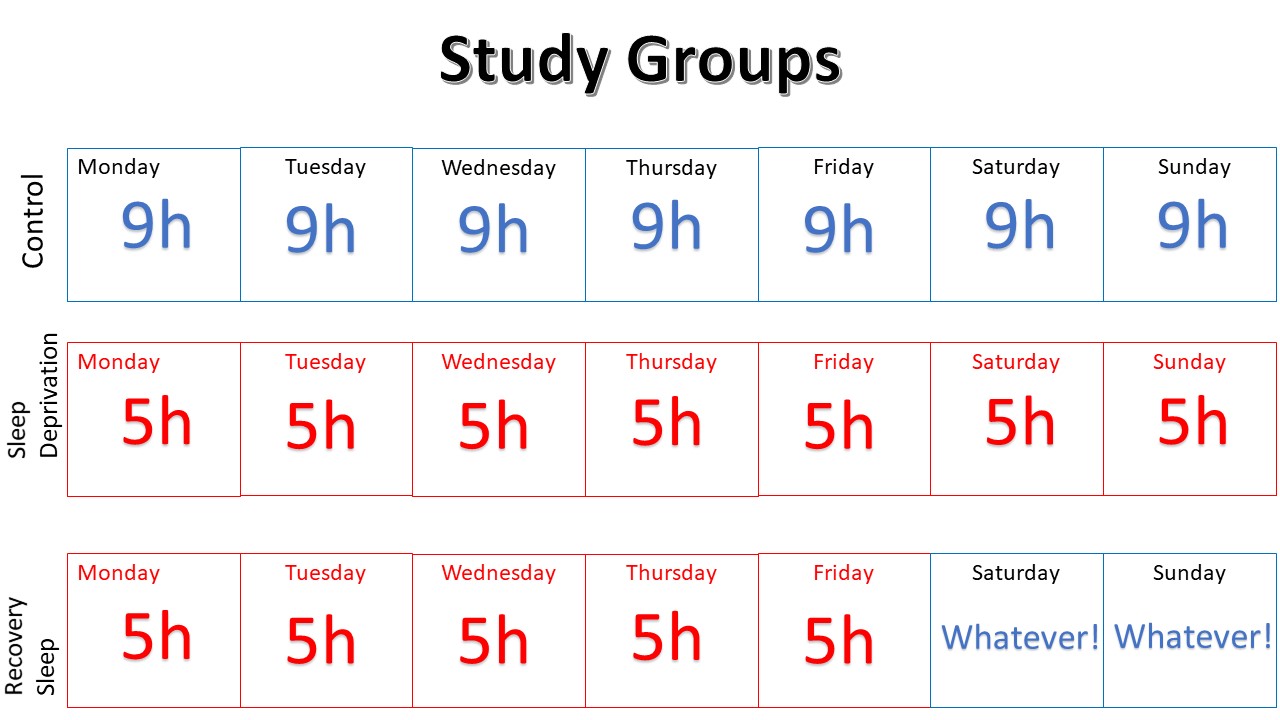

Then they were randomized into one of three groups.

The control group was put in bed for 9 hours a night, which sounds lovely.

One group was randomized to sleep deprivation – 5 hours in bed at night.

The final, and most interesting, group was randomized to sleep deprivation, but they were allowed to sleep in on the weekend – so-called recovery sleep.

Oh that lovely Sunday. I shall remember you.

I love this design. A good control group getting lots of sleep, a sleep-deprivation group with a fairly restricted schedule, and then a real-world group, representing what so many of us actually do.

I know from experience, dude. Here’s my fitbit data for the past week or so, showing I typically get around 6 hours a night but I had one glorious Sunday where my lovely wife let me sleep in.

It’s probably not enough. The researchers wanted to know how sleep deprivation and recovery from sleep deprivation affects our eating habits. The results were really fascinating.

I feel like I would eat way less if people were watching me.

First – sleep deprivation didn’t have a profound effect on calorie intake. All three groups ate a similar amount of calories on a day-to-day basis.

Despite that, the sleep deprived people seemed to gain a bit more weight – around 3 pounds over the course of the two-week study.

But why? Similar calories, more weight gain.

If you must eat, eat at the right time.

The researchers point out that after-dinner snacking was dramatically increased in both sleep deprivation groups. In fact, after-dinner snacks accounted for more calories than breakfast, lunch, or dinner in these groups.

Why does that matter?

Well, these people were eating when their bodies thought they should be sleeping – the researchers confirmed this by measuring melatonin level.

Melatonin onset (upward triangle) defines the start of biological night. Melatonin offset (downward triangle) defines the end of biological night. Because the (biological) night belongs to lovers. Because the (biological) night belongs to us.

You can see in this figure that the time of biological night (between the two arrows, when melatonin is peaking) occurs well before the participant got in bed and lasts well after they are woken up. In an e-mail to me, lead author Dr. Christopher Depner pointed out that in rodent models, eating during biological night leads to more weight gain than eating the same calories during biological daytime.

So that may be the crux of all this. When we sleep deprive ourselves, we snack. And we snack at the worst possible time.

But since this is Impact Factor we need to nitpick a bit. All of the findings I discussed represent significant changes from baseline within a study group. So when I said that the people in the sleep deprivation group gained more weight than those in the control group,

Let’s do a randomized trial but NOT compare the randomized groups. That’ll show those “scientists”.

what I should have said is that there was a statistically significant change in weight within the sleep deprivation group while there was not a statistically significant change in weight in the control group.

This is a subtle point, but key. The control group had fewer participants (8 vs. 14 each in the other two groups). With only 8 people in the control group, showing a statistically significant change is harder than it was in the other groups. The way to truly tell whether sleep deprivation affects weight gain compared to control would be to do a statistical test comparing weight across, not within, the two groups.

As far as I can tell, this test was not done, and I suspect it would not lead to statistical significance.

In other words, we can’t put this question to bed quite yet. Nevertheless, this study supports prior research showing that sleep deprivation has untoward metabolic effects including weight gain. And this study also suggests that weekend recovery sleep is not enough to turn this all around. That’s right, if you sleep deprive yourself during the workweek, you’ve made your bed. Now you’re going to have to lie in it.

This commentary first appeared on medscape.com.