Study Suggests Drinking Coffee Makes You Live Longer and It's Probably Not True

/The study of nearly 500,000 individuals found that more coffee drinking was linked to longer life. But it looks like it's not the caffeine that mediates the benefit.

Another day, another study extolling the virtues of coffee, this one suggesting that the dark, delicious drink protects against all-cause mortality. But there may not be as much joy in Mudville as it appears at first glance.

The study used a dataset called the UK Biobank and included 486,477 individuals. At baseline, they were asked about their coffee drinking habits and they were followed for a median of 7 years. The cool part about this study was that the participants had genetic testing done at baseline – this will become important in a moment.

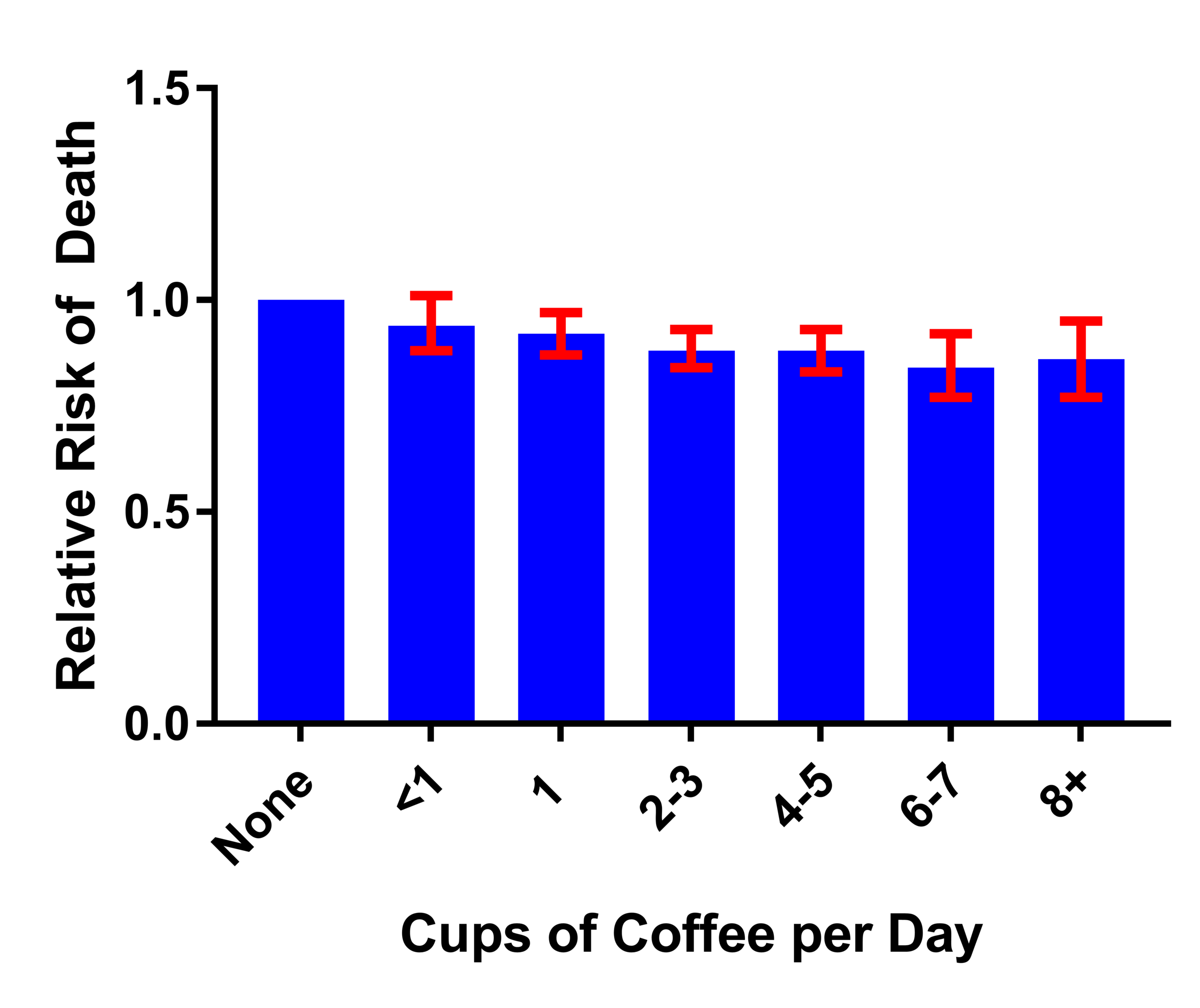

You can see the results here. Compared to non-drinkers, coffee drinkers had a lower risk of death. In fact, there was a bit of a dose-response effect here – with more coffee being more protective (Figure 1). Cheers.

Figure 1

But there’s a bit of a problem in this study – something that, frankly, makes me a skeptical about other coffee studies too.

Remember how they had genetic data on these participants? The researchers used the genetics to determine how fast they could metabolize caffeine.

Go with me on this for a minute.

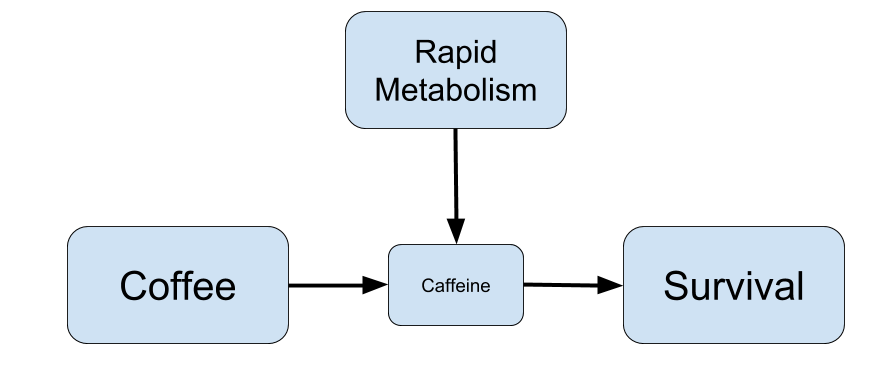

Figure 2

The principal biologically-active ingredient in coffee is caffeine. If greater caffeine exposure prolongs your life, than coffee-drinkers would live longer (Figure 2).

Figure 3

But those who metabolize caffeine more rapidly would not be benefitted by coffee as much – they’d burn it away before it did all it’s good stuff. The link between coffee and survival would not be as strong (Figure 3).

This study did NOT show that effect.

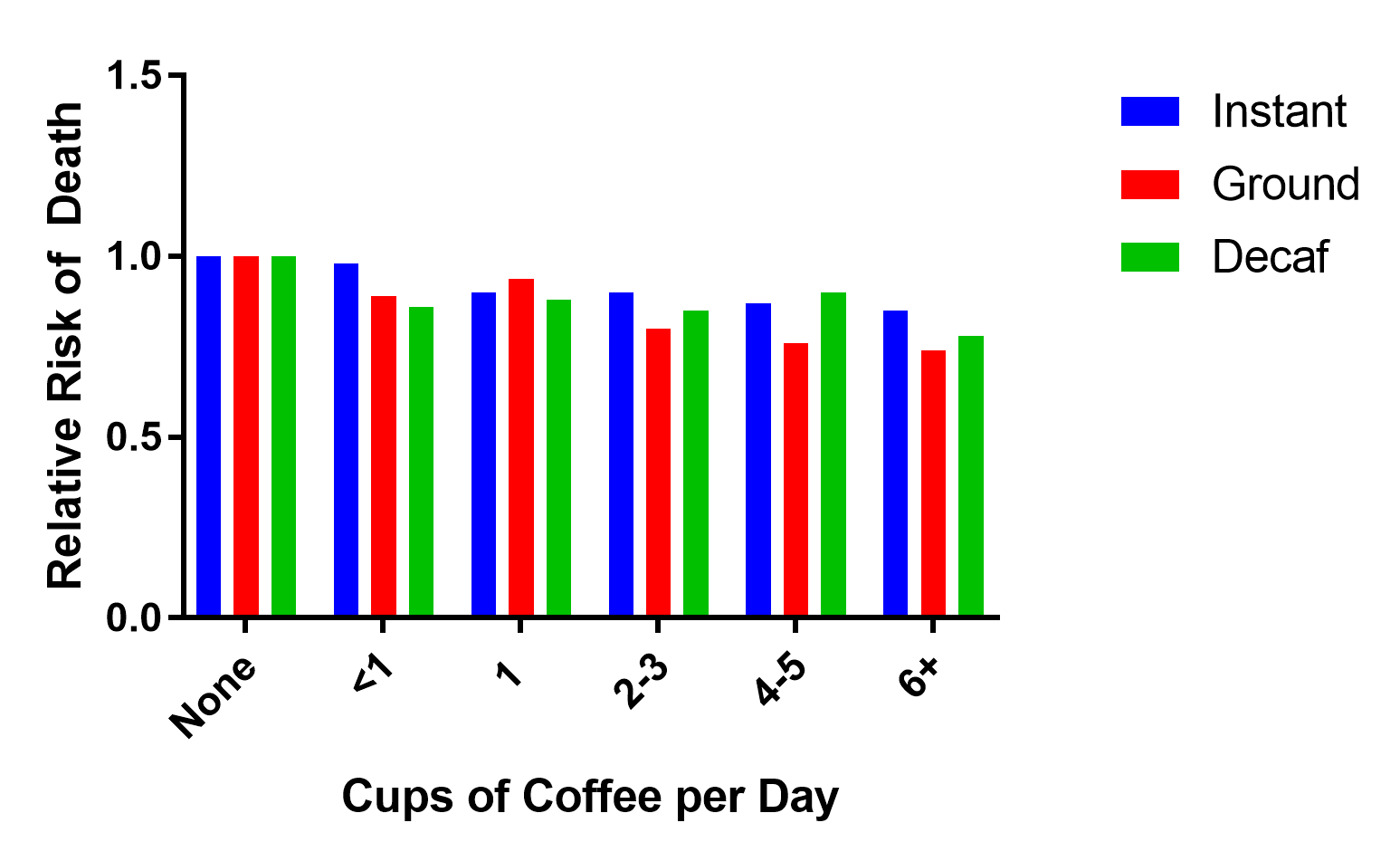

In fact, the benefit of coffee was pretty similar whether you drank instant coffee, ground coffee or decaffeinated coffee – which is – to quote David Letterman just useless warm brown water (Figure 4).

Figure 4

The authors conclude: “These findings suggest the importance of non-caffeine constituents in the coffee-mortality association”.

In other words, it’s not the caffeine, it’s other compounds in coffee that give it this great effect.

In my opinion, if it’s not the caffeine, it’s not the coffee at all. Here’s why:

Caffeine is a drug that has significant, measurable biological effects. The other compounds in coffee, if they do anything, have subtle, difficult-to-measure effects. But now we’re being asked to assume that the effect of caffeine on mortality is essentially a wash, allowing these other subtle effects to be unmasked.

It’s like if I mixed cocaine with vitamin C and told you that we could measure the effect of vitamin C by seeing how people respond to the mixture. The active ingredient is just going to overshadow everything else.

So I’m putting a marker down, mostly to see what people come up with as a counterargument – if one observes a benefit in a population associated with consuming a food or beverage, and the benefit is not mediated by the active ingredient in that food or beverage, the finding is likely due to unmeasured confounding.

In other words, I think coffee is in the same camp as red wine: the observed benefits are likely due more to the type of person who drinks it than what’s actually in the drink.