New Drugs Hold Real Promise for Metastatic Melanoma

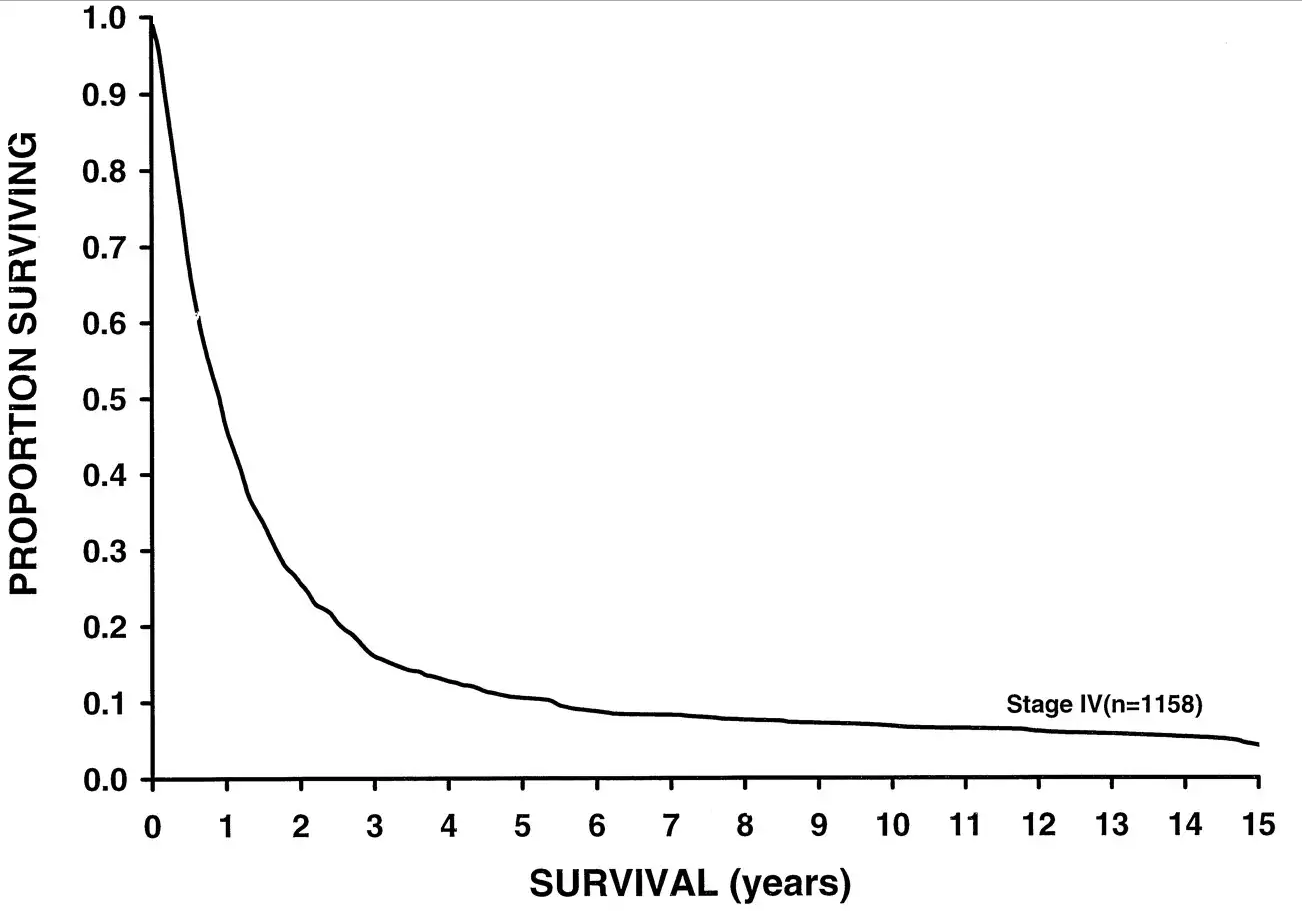

/I'm going to show you a survival curve for metastatic melanoma.

This data was analyzed in 2001, but sadly, even current 5 year-survival for metastatic melanoma sits around 15%. But some new drugs might change this.

For the video version of this post, click here.

Here's a chart examining Melanoma-associated mortality rates over time:

Compare that to breast cancer, which has seen some dramatic therapeutic advances over the past few decades:

But melanoma is riding a wave of novel immunotherapies that hold promise to change the treatment landscape substantially.

Appearing in the Journal of the American Medical Association is a type of study we don't see too much of these days. It's not really a clinical trial. It's not really a meta-analysis. Frankly, I'm not sure what to call it – an aggregate analysis perhaps?

The study examines 655 patients treated with the PD-1 inhibitor pembrolizumab from 2011 to 2013. Yup, that's the same pembrolizumab which was used so successfully to treat this charming former president:

A brief aside here. Pembrolizumab is a monoclonal antibody directed towards programmed cell death protein 1, PD-1. PD-1 acts to prevent immune cells from attacking your own cells – it's an immune "checkpoint" making pembrolizumab one in a class of "checkpoint inhibitors". Basically, by blocking PD-1, pembrolizumab allows your immune system to attack your own cells. Not something you want under ordinary circumstances, but perhaps beneficial when your own cells have turned against you.

Merck has bet big on pembrolizumab, with clinical trials ongoing or planned in melanoma, non-small-cell lung cancer, small-cell lung cancer, ovarian cancer, glioma, colorectal cancer, and on and on. What happens when a company is doing so many trials like this is a kind of fractionation, where you lose the aggregate knowledge of patient experiences because they are spread out across so many trials.

So I was gratified to see this aggregate analysis which examined patients with advanced melanoma receiving pembrolizumab across four different trials. See, if you do four trials, and one is nice and positive, and the others are equivocal, and you are a for-profit drug company, maybe you're more likely to try to get that positive trial into some high-profile journal, and let the others either languish in peer-review hell or get published in an out-of-the-way rag.

What we get in JAMA, though, is a study with adequate power to demonstrate that pembrolizumab might make a difference.

Among all the patients treated with pembrolizumab (and yes, there is no control group reported here), the objective response rate was 33%. The median overall survival was 23 months, and 31 months among those for whom pembrolizumab was the first systemic cancer therapy. Compared to the historical median survival of under a year, this represents a substantial improvement.

Interestingly, among those who responded to the drug initially, the duration of response was fairly long. In fact, at 2 years, around 70% of people who initially responded to the drug were still responding. This is a good thing, as it demonstrates that development of resistance to therapy might be limited.

Now, before we bestow too many accolades on Merck for giving us this aggregate data, we might ask whether they would have been as forthcoming if the trials weren't quite as successful. But, placing cynicism aside for the moment, it seems that this drug, or one of its competitors will have a place at the table in the treatment of advanced melanoma.